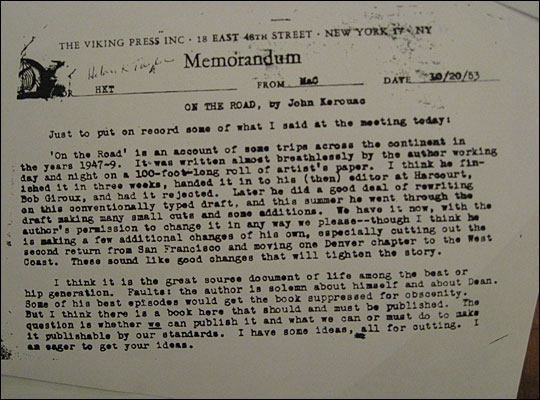

Lord pitched On the Road to publishing house after publishing house, only to be told the manuscript was "unpublishable." He says one of the book's biggest advocates was author and editor Malcolm Cowley, an adviser to Viking Press — and even he had reservations, expressed in an internal memo dated 1953, with a paragraph headlined "Faults":

"In the book, it says 'My aunt once said the world would never find peace until men fell at their women's feet and asked for forgiveness, but Dean knew this,'" Canary points out. In the scroll, though, the passage went on:

Kerouac reportedly complained to Allen Ginsberg that Viking botched his manuscript. Lord, his agent, says the editing was handled gracefully.

But On the Road's journey didn't end there. Viking sent the manuscript to lawyers who wanted the names of real people, such as Ginsberg and Cassady, changed for fear of libel. Other things were edited, too. Conservator Jim Canary is fond of pointing out the differences between the original scroll and the published book.

Kerouac Audio and Video

Between 1951 and 1957, Kerouac tinkered with as many as six drafts in a desperate attempt to get editors to accept his work, according to Sampas. A letter from Kerouac to fellow beat writer Neal Cassady, dated June 1951, complains about a rejection from one publisher and mentions that Kerouac is shopping for an agent.

But the scroll: That part's true. Jim Canary, the Indiana University conservator who's responsible for its care, says Kerouac typed about 100 words a minute, and replacing regular sheets of paper in his typewriter just interrupted his flow — thus the scroll.

"I didn't ever dream that this would be the huge seller that it has become — although I didn't think it wouldn't — but I felt that Jack's was a very important new voice and he ought to be heard," Lord says. "And I was totally convinced of that."

And so it went, until the mid-'50s, when a new crop of young, receptive editors — and enthusiastic response to On the Road excerpts printed in The Paris Review — helped persuade Viking to publish it. They offered a $900 advance; Lord talked them up to $1,000, but the publisher, fearing the author would squander the money, insisted on paying it out in $100 installments.

Papyrus

The use of papyrus as a writing material originated in Egypt and has been traced back to A.D. 2500. In the New Testament days it was still most popular writing material.

Do you know the writing materials used for the first Holy Bible?

Pens

Pens were simply made from dried reeds which had been cut to a point and then carefully slit at the end. Quill from bird feathers later replaced reed pens.

On the scroll the text was written in columns about 2 ½ to 3 inches wide, and just over ½ an inch apart from one another. The text was usually only on one side of the scroll, but an exception to this is alluded in the Holy Book of Revelations 5:1, "and I saw in the right hand of him that sat on the throne a book written within and on the backside, sealed ith seven seals."

Subscribe to the Diocese's Email List

Papyrus "paper" was from the Egyptian papyrus plant. Scrolls of papyrus were rolled out horizontally rather than vertically. They were about 10 inches high and up to about 35 ft in length.

Vellum and parchment

Animal skins used as writing material are known as vellum and parchment. Some such leather scrolls are still in existence and date back to 1500 B.C. Vellum refers to the best quality animal skins and came from calves, while parchment refers to all other animal skin used in paper making such as bulls and goats, and was inferior in quality to vellum.

From Scrolls to Books

In Old Testament and New Testament times the papyrus paper was made into scrolls by joining the Papyrus sheets to each other. Later on papyrus sheets were used in book form, when books replaced scrolls.

Papyrus

The use of papyrus as a writing material originated in Egypt and has been traced back to A.D. 2500. In the New Testament days it was still most popular writing material.

Do you know the writing materials used for the first Holy Bible?

Pens

Pens were simply made from dried reeds which had been cut to a point and then carefully slit at the end. Quill from bird feathers later replaced reed pens.

On the scroll the text was written in columns about 2 ½ to 3 inches wide, and just over ½ an inch apart from one another. The text was usually only on one side of the scroll, but an exception to this is alluded in the Holy Book of Revelations 5:1, "and I saw in the right hand of him that sat on the throne a book written within and on the backside, sealed ith seven seals."

Subscribe to the Diocese's Email List

Papyrus "paper" was from the Egyptian papyrus plant. Scrolls of papyrus were rolled out horizontally rather than vertically. They were about 10 inches high and up to about 35 ft in length.

Vellum and parchment

Animal skins used as writing material are known as vellum and parchment. Some such leather scrolls are still in existence and date back to 1500 B.C. Vellum refers to the best quality animal skins and came from calves, while parchment refers to all other animal skin used in paper making such as bulls and goats, and was inferior in quality to vellum.

From Scrolls to Books

In Old Testament and New Testament times the papyrus paper was made into scrolls by joining the Papyrus sheets to each other. Later on papyrus sheets were used in book form, when books replaced scrolls.

The scroll is the standard way of preserving a text in antiquity

Scrolls are usually wound around a central baton, the umbilicus

- Maps (itineraries for pilgrimages to Rome, the Holy Land, etc.

1. Scrolls whose length is not known at the beginning.

What is a scroll?

Scrolls continued to be made and used throughout the Middle Ages. Why was the scroll preferred to the codex? There are four reasons that suggest scroll format, and these account for essentially all medieval scrolls.

- Scrolls that record edicts, receipts, lists (see the manor court roll on display in the Houghton Library Exhibit)

- Mortuary scrolls

- Amulets, prayers, and charms (such as the Arma Christi rolls, and the Life of St. Margaret which, if worn on the body, protects during pregnancy)

- Processional scrolls, used when a full liturgical book is too much

- Actors’ scrolls (rôles)

- Poetry (useful in recitation: see the Ganymede and Helena roll on display)

Scrolls continued to be made and used throughout the Middle Ages. Why was the scroll preferred to the codex? There are four reasons that suggest scroll format, and these account for essentially all medieval scrolls.

- Maps (itineraries for pilgrimages to Rome, the Holy Land, etc.

The scroll is the standard way of preserving a text in antiquity

Scrolls are usually wound around a central baton, the umbilicus

When were scrolls used?

- Amulets, prayers, and charms (such as the Arma Christi rolls, and the Life of St. Margaret which, if worn on the body, protects during pregnancy)

- Processional scrolls, used when a full liturgical book is too much

- Actors’ scrolls (rôles)

- Poetry (useful in recitation: see the Ganymede and Helena roll on display)

By the fourth century C.E., however, the codex became the most usual way of preserving a text

- Liturgical scrolls (see the Greek liturgical scroll on display)

- Reports of church councils